A few months ago, on the New York subway, I looked up at the woman sitting opposite me, and found my eyes drawn to her cap: “I don’t give a F**K,” read big white letters stitched into navy blue cotton.

Three million New Yorkers ride the subway every day. On some days, it feels as though a quarter of them have a stupid slogan of one kind or another embroidered on their caps. And yet, there was something about this particular woman, proudly sporting this particular slogan, that felt to me totemic of this particular moment in American life.

I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost.

Thinking highly of your compatriots and caring deeply about the fate of your country were once seen as virtues; now, such sentiments are rejected as proof of naïveté, perhaps even of an insidious commitment to the status quo. A young politician’s promise of “Hope and Change” once inspired America; today, many young Americans pride themselves on having awoken to the fraudulence of such illusions. Popular culture was once ironic and self-aware, poking fun at the absurdities of elite progressives even as it affirmed much of their worldview; today, it is unremittingly censorious, ever ready to sit in judgment on anyone who has a divergent opinion.

I was raised in the Germany of the 1980s and 1990s. Born to Jewish immigrant parents, I never quite felt like I belonged in a country still marked, in those later postwar years, by the extreme levels of homogeneity forged through the genocides and expulsions of the 20th century. But though not fully of the place, I was shaped by many of its instinctive habits of mind: the tendency to critique rather than enthuse; the sense that things have their place, and people too; the deference to hierarchy and to the prerogatives of advanced age.

I fell in love with America in good part because it promised to open up to me a more fluid and variegated, more entrepreneurial and optimistic world. New York, in particular, was home to millions of people drawn from all corners of the globe. And while much of the city was split into different immigrant enclaves, its collective spirit felt freewheeling, its dominant culture genuinely cosmopolitan.

These commitments were evident in the popular culture of the time. In grad school, I often watched one of the biggest sitcoms then on television: 30 Rock, a show which poked equal-opportunity fun at its diverse cast of absurdist characters. This ability not to take yourself too seriously very much extended to their preening political commitments, which were affectionately ridiculed without ever being disowned.

In one episode, NBC promotes a new superhero character, called Greenzo, who is supposed to spur viewers to take action for the environment. But the narcissistic actor playing Greenzo soon becomes so self-righteous that he makes everyone hate him. “Here’s a tip, Cerie,” he tells an assistant when she leaves the door of the office fridge open too long for his liking. “Decide what you want before you open the refrigerator. You just released enough hydrofluorocarbons to kill a penguin.” Today, that scene might be perceived, and denounced, as a form of anti-woke agitprop; back then, it was rightly read as progressive filmmakers warning their progressive viewers about the dangers of progressive finger wagging.

30 Rock was no outlier. A similar spirit of irreverent humanism also grounded TV shows like The Office and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, animated series like Family Guy and South Park, hit musicals like Avenue Q and the Book of Mormon, and movies like Borat or Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle. In 2007, the magazine most widely perceived as being on the cutting edge of cool was VICE, a publication that prided itself in breaking taboos and refusing to accept any stricture, moral or religious, on the kind of content it put out.

What’s striking about the dominant cultural products of those years is just how hard it would be to get them commissioned today. Tellingly, episodes of 30 Rock, The Office and It’s Always Sunny have been removed from streaming services since the “racial reckoning” of 2020.1

In the fall of 2007, George W. Bush, about to enter his last year in office, was growing deeply unpopular. The spirit of unity that animated the country after 9/11 had long since given way to the acrimony of the Iraq War and widespread shock at the government’s incompetence during Hurricane Katrina. On Wall Street, a few shrewd traders were starting to recognize the signs of an impending crash, one that would ultimately grow to epic proportions.

I would never mean to deny that the United States suffered from serious problems when I moved here, nor that the country has in many important ways—such as the introduction of same-sex marriage—transformed for the better since then. But there is one key difference: Back then, the country’s problems seemed to make up neither its essence nor its inevitable future. Even in the elite left-leaning milieus into which, without quite realizing it at first, I was initiated as a graduate student at an Ivy League school, most of my friends professed a deep-rooted faith in America’s founding principles, and retained an instinctive belief in America’s future prospects. The basic soundtrack of American life—perfectly compatible with plenty of irony and self-criticism (or so it seemed at the time)—was pride in what the country had been and in what it was yet to become.

Möchten Sie meine Artikel und Gespräche auf Deutsch direkt in Ihre Mailbox bekommen? Klicken Sie diesen Link und schalten Sie unter Notifications “auf deutsch” an! 🇩🇪

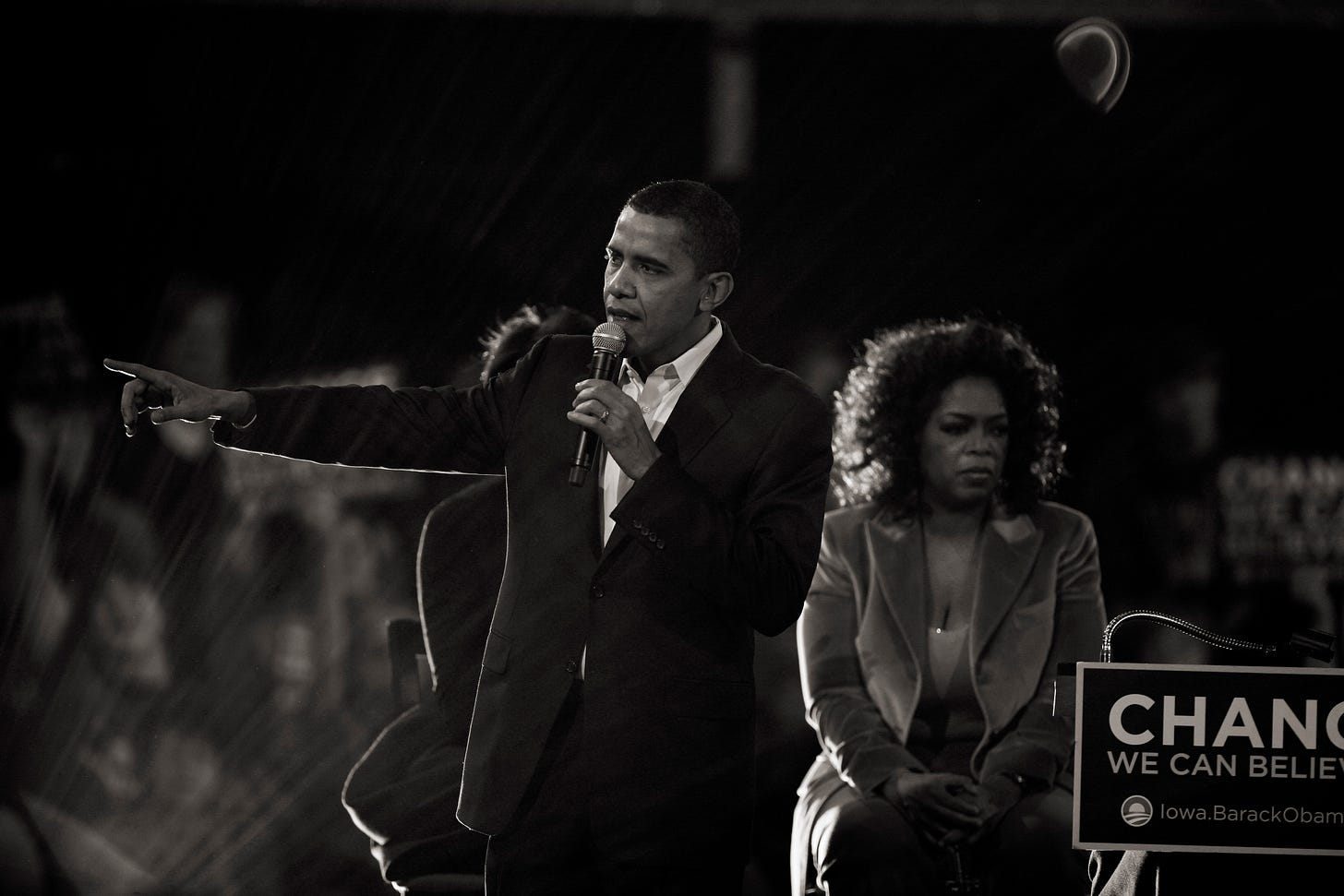

During my first months in the country, it was Barack Obama, then still a longshot contender for the Democratic nomination, who most personified this self-confident spirit. His own biography was testament that the country contained multitudes, multitudes that could create something at once completely idiosyncratic and totally American. Notwithstanding Obama’s skeptical stance towards American exceptionalism, his message was built on the assumption that the arc of American history would “bend towards justice.” In his rousing speeches, he addressed the country’s failings in a forthright manner—but always insisted that its true nature consisted in the ability to right those wrongs.

In the first years after 2007, this deep-seated optimism about America’s nature still set the theme for the country’s soundtrack. Despite Bear Stearns’ collapse and the Great Recession, despite the rise of the Tea Party and Donald Trump’s insinuations that Obama had forged his birth certificate, the country still felt dynamic and self-assured. And then, with remarkable abruptness, a very different tune started to play.

A few months ago, a visiting lecturer asked a room full of undergrads at City College Of New York which public figures they most admired. City College is one of the few institutions of higher learning that still has the distinction of helping scores of working-class kids—many of them drawn from the unfashionable outer boroughs of New York, and born to immigrant parents who drive cabs or do menial labor—make their way into the upper-middle class. So, sitting in the audience, I expected that the students would have a healthy dose of skepticism towards America’s high-and-mighty, mostly naming musicians, athletes and influencers, perhaps with one or two activists or politicians thrown into the mix.

The answer the students actually gave revealed a depth of distrust and disillusion for which I had not been prepared: They insisted—without hesitation or qualification—that there isn’t a single person in public life they admire.

In a way, this cynicism is an understandable reaction to the evident corruption that American public life has undergone over the course of the last two decades. There is a theory according to which each president is, in key respects, an inversion of his immediate predecessor. And it is certainly true that Trump replaced Obama’s optimism and faith in America with a hostility to the country’s political traditions and an apocalyptic vision of its present condition.

There is something deeply American about Trump’s life and career, including a lack of respect for decorum or high culture that harkens back to the longstanding new world skepticism about the old world (a skepticism for which, as an immigrant from the latter to the former, I retain a certain fondness). But his political legacy is to have taken the Republican Party from an American tradition of conservatism towards something more closely resembling a European tradition of right-wing reaction; the assault on the Capitol inspired by Trump was, for all his protestations, thoroughly un-American.

Tragically, Trump’s enormously corrupting influence on American society has turned out to extend beyond the ranks of his most ardent supporters. The transformation of the left and the mainstream—of equal concern to me, if only because these are the milieus which once constituted “my” America, the part of the country in which I felt at ease and at home—has in some ways been just as striking.

Souhaitez-vous—ou quelqu’un que vous connaissez—avoir accès à tous ces articles et conversations en français? Cliquez sur ce lien et activez “en français” sous Notifications! 🇫🇷

The belief that America is defined by its perfectibility has given way to an insistence that America is defined by its past and present injustices. The quiet confidence in a better future which I found so alluring when I first arrived has transmuted into a self-congratulatory embrace of doomscrolling and doomsaying. The attempt to empathize with those who hold different political views, once recognized as a key civic virtue, is now condemned as a moral vice. The insistence that Americans are more defined by their commonalities than their differences has given way to an identitarian tribalism that even organizes rallies for a presidential candidate by self-segregating category of gender and race. The cumulative impact of all of this is a deep-going cynicism, shared even by those, like the upwardly mobile students at City College, who have good reason to believe that they themselves have every chance of achieving the American Dream.2

Under the new dispensation, a refusal to give into this kind of smug rage has—as I realized a couple of months ago, when I interviewed Daryl Davis—come to feel strangely old-fashioned, and perhaps even a little counter-cultural.

Davis is a black musician who made his name as a versatile piano player, as comfortable playing jazz and boogie-woogie as country music. The true passion of his life, however, consists in his political work. After a patron at an all-white bar in which Davis was performing revealed to him that he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan, they struck up an unlikely friendship, and Davis set out to interview other members of the organization. Over the following years, Davis inspired dozens of white supremacists to leave the movement. He is now the proud owner of 25 KKK robes, all of them given to him by former members of the organization as a sign of their respect.

A key reason for his success, Davis told me when I interviewed him for my podcast, is that he insisted on treating the racists he encountered as equals—nothing less and nothing more. When he first met them, he would shake their hand and look them in the eye. Then he would ask them, with full sincerity, how, never having met him before, merely on the basis of the color of his skin, they could hate him.

Davis is no fool. He recognizes that not everybody is open to changing their minds. And while he sets out to encounter everyone with an open heart, he is no pacifist either. When someone physically attacks him, he told me with evident pride, he gives as good as he gets.

And yet, talking to him in this cultural moment, Davis’s fundamental optimism struck me as hopelessly anachronistic. His faith that even people who had done awful things could be subject to redemption, and his insistence that his dignity was so deep-seated that it could not be destroyed by a bigot’s hatred, felt like the product of an altogether more humanistic moment in American history. While talking to him, I suddenly realized that he is a figure from a bygone era: a reminder of an America that ceased to exist sometime between 2007, when I arrived in the country, and today.

I still love America. And yet, with each passing day, my love feels more nostalgic, like the affection you feel for the past incarnation of a friend who, having taken a wrong turn in life, has grown unbecomingly bitter—one that you’re incapable of letting go even though a big part of you feels you probably should.

But might the pervasive pessimism of this moment be making me, too, overly pessimistic?

A country’s mood can fluctuate from decade to decade. Vibe shifts happen on the regular. Long-standing cultural repertoires are, however, slow to change. And for all the tension and the dysfunction that you feel in everyday life, something of America’s optimistic spirit still goes strong.

So even though my heart despairs about the state of the country these days, my head tells me to keep up hope. America is at a low point. Many of the things that made me fall in love with this country are at present conspicuous by their absence. There’s every reason to think that things could get even worse in the next months and years. But just as the night is darkest before dawn, so too today’s barren cultural landscape may just create the empty space for a genuine renewal. And if there’s one thing that all who love America should remember, it’s that this country is too wild and too vast, too vibrant and too whimsical, to count it out prematurely.

It is also telling, in this respect, that some of the most vibrant parts of today’s popular culture consist in decades-old television shows that have been “grandfathered” into this moment. Family Guy (first aired in 1999), South Park (first aired in 1997) and even The Simpsons (first aired in 1989) can continue to be irreverent despite the occasional attempt to censor their more “offensive” content because they have been part of the cultural landscape since before the new spirit of censoriousness took over; newer shows are far less edgy, perhaps because the relevant committees refuse to greenlight similar efforts, or because a younger generation of creative minds engages in anticipatory self-censorship.

Again, the transformation of television, including the prestige dramas which have, perhaps prematurely, been hailed as the 21st century incarnation of the novel, is especially telling. The most acclaimed shows of the 1990s and 2000s were premised on the assumption that even the lowliest Americans, from mobsters (The Sopranos) to drug dealers (The Wire), had a rich interior life with which viewers might come to empathize. The specimens of the form that have won all the prizes of late, like Succession, are based on the opposite assumption. They teach us that even the most powerful and influential Americans are thoroughly incompetent and utterly immoral. Its fictional worlds are populated by characters so repugnant that any pleasure there may be in watching them consists, for the most part, in the smug reassurance that, whatever our own personal or political imperfections, at least “we” are better than “those people.”